Already a member? Log in to the Member Site at members.mastery.org.

Mastery Transcript and the Evolving College Admissions Process

August 28, 2021

Demystifying Mastery Learning: A Conversation with Utah Educators

October 27, 2021Learning from Student Work: Implications for Mastery Learning at Phillips Academy

Spending the last few months meeting with schools and exploring pathways for using the Mastery Transcript has been one of the most incredible learning experiences for me. The opportunities discovered and cultivated by our member school colleagues are innovative, thoughtful, strategic, and courageous. Even if entire schools have not yet transitioned to mastery learning, pioneers are designing these pathways with an eye towards deeper learning for students, generating models for faculty, and proving concepts that work for learners and their families. The Workshop at Andover is one of these pathways that I return to repeatedly when I’m sharing MCA models in MTC’s Mastery Credit Library with our member schools.

The Workshop’s mastery credits are small yet intentionally set, at the same time bold and transdisciplinary, yet minimalist and nuanced. Learner outcomes from this new venture have provided a clear proof of concept that a competency-based approach can have a lasting impact on students, as you’ll read below. We’re grateful to Andy Housiaux, Director of The Workshop and the Tang Institute at Phillips Academy, for sharing these insights and further inspiration for building a strong foundation for mastery learning with smaller-scale approaches.

The Workshop at Andover is a term-long, immersive learning experience for spring term seniors. It represents a significant departure from their previous schooling: they drop all of their classes and instead work with a cohort of students on a series of interdisciplinary projects. Just as important, traditional grades are replaced with a system of ongoing feedback and self-reflection in relation to a series of mastery credits.

These mastery credits fall into three broad areas. First, there is learning to learn, which focuses on metacognition and helping students better understand how their minds and brains work. Second, there is practice and craft, which looks to Ron Berger’s ideal of an Ethic of Excellence; Finally, there is civic engagement, which gives students ways of reflecting on their own agency and social location as they attempt to engage thoughtfully in their many communities.

This blog post will highlight exemplary student work as it relates to each of the three mastery credit areas. It will also flesh out important questions about student voice and choice, assessment, and ways in which students saw themselves reflected in the work they do.

Learning to Learn

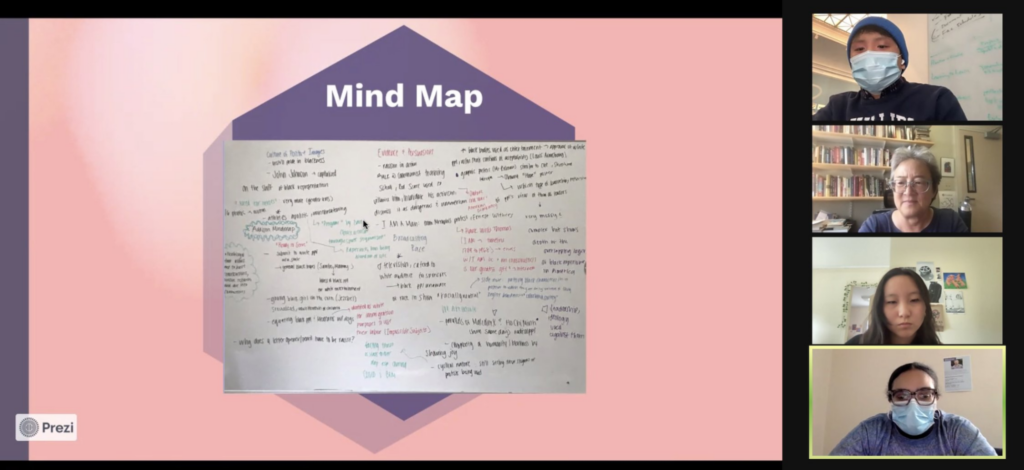

Educational psychologist Daniel Willingham writes often that experts and novices think differently from each other. According to Why Don’t Students Like School?, one of the ways they differ is with their use of mental models, or schema. Put simply: experts have well-organized mental maps of a discipline, while beginners are much more likely to see random facts rather than the underlying structure. For Angie ’21, this insight led to a transformative understanding of her learning and how she learns. In a midterm presentation to our community on what she learned so far, she told her peers, “I’ve learned more about how I learn in these past five weeks than I had in the previous four years.” The linked tweet shows clearly just how much Angie learned by organizing her knowledge for herself, getting a clearer sense of what she knows and how this knowledge relates to itself.

This learning exemplifies one of our mastery credits in the learning to learn area: “I can reflect on what I know and the limits of what I know.” As she learned more about schema and applied what she learned to her research on race, art, and the Civil Rights Movement, she began to see connections and gaps in her knowledge. As a result, she had a clearer sense of what she knew and where she needed to do more research. This more mature self-understanding is evidence of thinking more like an expert, and less like a novice. Just as important, it shows a student who is becoming more intellectually autonomous, able to use her well-organized, existing knowledge as the basis for subsequent research and learning.

Practice and Craft

How can we help students cultivate an ethic of excellence? There are many ways to do so, of course, but we found inspiration in Ron Berger’s use of exemplary models of work with his students. As a teaching team, we asked students to study examples of excellent work – and then to reflect not just on the content of the piece, but also on the authorial choices and implicit structure that helped make the piece shine.

One of our mastery credits in this area says that students can “analyze examples of outstanding work to infer the qualities that would constitute excellence in [their] own practice.” This credit is important for two reasons: one, we want to help students develop judgment. What makes something excellent? What makes one piece of writing more effective than another? While some of these questions are about taste and preference, others are connected to aesthetic and academic judgment.

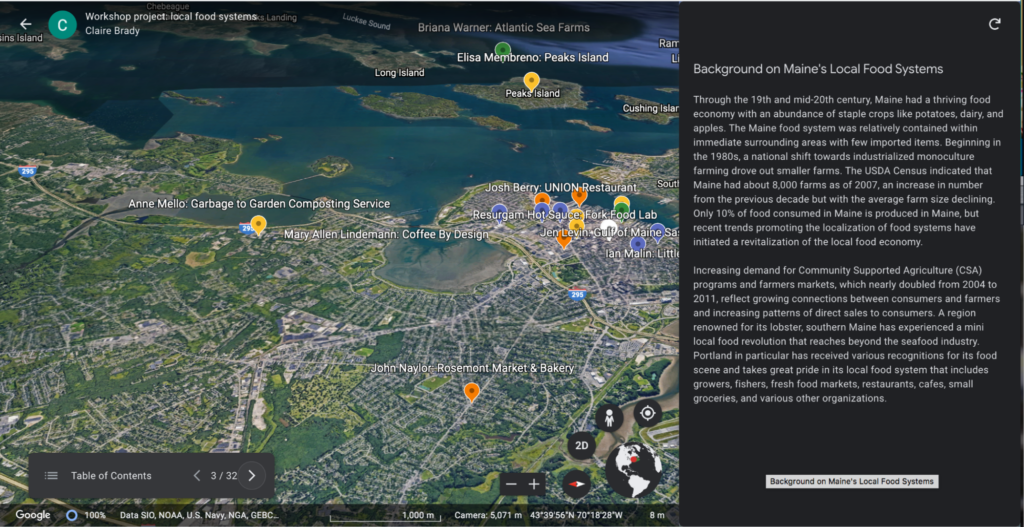

Just as important, though, this mastery credit emphasizes transfer. Students do not do this exercise merely to become good students of someone else’s work. Rather, they do so with an eye to understanding how to make similar kinds of moves in their own writing. Claire, ’20 had the idea to map out the food supply chain of southern Maine during her time in the Workshop. As she studied various photo essays online, she came to realize the strengths and weaknesses of that approach. She came to appreciate the way in which such narratives combined visuals and text, but she also realized that she needed to root her project much more cartographically to orient her audience to the physical distances, links, and connections between various nodes of the food supply chain.

Civic Engagement

Like most schools, Andover aspires to prepare students for global citizenship. We wanted to think in a bit more detail what such engagement would consist of. In particular, we wanted to think about what informed and appropriately humble engagement with a community would look like. How might we encourage our students to engage in their work with questions and not answers, and to see themselves as engaging with and contributing to a slice of a complex problem, rather than hubristically thinking they can tackle massive, systemic challenges in a one-term undertaking?

Two related ideas were particularly relevant for our work here. The first lays out an ideal of research-based, reflective citizenship: “I can research and synthesize information from multiple disciplines to enhance my awareness of the complexity of an issue or a problem in my community.” The second asks students to reflect on their own identities and possible blind spots: “I can bring an awareness of my own social location and possible biases and assumptions to my interactions with others.”

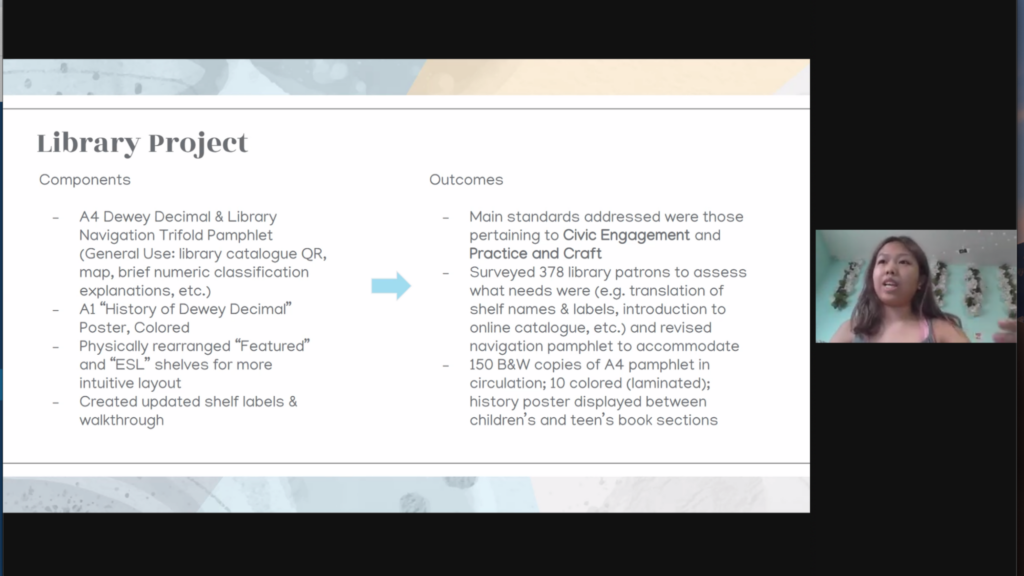

Several students did exemplary work in this regard in our first two years, but a recent project done by Catherine ’21 particularly stands out. Unable to return to campus for the spring term, Catherine was one of two remote participants in the spring term Workshop. To her credit, she applied the principles of the program to her local context in California and undertook a term-long project with her local public library – a place she had volunteered frequently when she was growing up.

As a long-time patron of and volunteer at the library, Catherine had a strong familiarity with the place. However, as she looked at this library with fresh eyes – and with questions around access and equity in particular – she saw ways in which she might be able to collaborate with the library staff to reimagine physical space in the library and help patrons better orient themselves to the collection. In close collaboration with senior library staff there, she administered a survey to nearly 400 library patrons about their browsing habits and used that information to think about what parts of the collection were being used the most. She and her collaborators at the library realized that shifting the physical layout of two sections – recent acquisitions and books for ELL readers – would improve the browsing experience for each group. Just as important, Catherine helped to create a series of guides for the ELL population that accesses her library, orienting them to both the physical layout of the space and the organization of the Dewey Decimal System.

Take-Aways

This student work shows the deep ways in which students were able to make meaning with complex, interdisciplinary topics by reflecting on their own learning, cultivating habits of excellence, and engaging in authentic partnership with their communities. When we talk about mastery credits with our students, we often do so in the language of habits. Our mastery credits are our vision of the first principle of the Coalition of Essential Schools: “Schools should focus on helping young people learn to use their minds well.” Our three mastery credit areas are of course not the only vision for this kind of work, but coming at the end of a rich and robust high school experience, they work well for us. They ask students to cultivate the habits of pausing and introspection, of revising and seeking out excellent examples, and of reflective collaboration with one’s own community.