Already a member? Log in to the Member Site at members.mastery.org.

Member Voices: The Ground Game

May 10, 2019

The Mastery Transcript: Game Changer

May 17, 2019Mastery Transcript Takes Center Stage at Northeastern

During the coming weeks, more than 60 students from a handful of schools across the country will be working with their teachers and counselors to start preparing their Mastery Transcripts for college applications.

On May 6 and 7, 2019, more than a hundred participants from Mastery Transcript Consortium™ member schools filled up the Raytheon Amphitheatre at Northeastern University in Boston for MTC’s fifth and final Site Director meeting of the school year. The first university to host MTC on campus, Northeastern has long been a leader in innovative education, with “more than a century of experience in learning that happens everywhere, both inside and outside the classroom,” said Liz Cheron, dean of admissions at Northeastern, who opened the two-day meeting. A member of MTC’s Higher Education Working Group (HEWG), Cheron was also featured on a panel at Northeastern about college admissions and the Mastery Transcript. Cheron expressed excitement about the depth of student profile that the Mastery Transcript will provide to admissions officers, while also providing a consistent, easy-to-read transcript format.

“The Mastery Transcript can help us even better identify the students who are really going to light this place up,” she said.

During the meeting, MTC also announced that the state of Utah had recently become MTC’s first state partner, with 23 of its public high schools already signing on for membership. Todd Call, competency-based learning coordinator, and Sydney Young, digital teaching and learning specialist, who will be guiding the coordination efforts with the Utah State Board of Education, were both present.

“We are excited to be here to learn from you all and for the opportunity to share in this network,” said Call.

A feature presentation about the “why, what, and how of mastery learning” was given by Chris Sturgis, a leader in mastery-based education who cofounded CompetencyWorks, serves on MTC’s Advisory Council, and is principal of Learning Edge. Her workshop engaged the audience of educators and administrators in exploring ideas and strategies for progressing their school’s journey to mastery-based learning and the Mastery Transcript. Following are excerpts of her remarks, which were originally published on Learning Edge.

A Conversation on the Why, What, and How of Mastery Learning

Presentation by Chris Sturgis

Today, what we will be doing is exploring several questions such as:

Why is mastery learning valuable? Why change?

What are the core elements of your mastery system going to be?

How

- How might the traditional beliefs trip you up?

- How will you leverage the Mastery Transcript? How will you change your school?

- How will you lead the effort to transform your school?

You most likely have your own questions you want to address during our two days together, so you might want to jot those down on the reflection tool.

Our first discussion is about why and how we need to change our schools. Many schools jump into mastery-based learning and start to change structures. You cannot create competency frameworks or change grading without taking the time to lay the foundation of understanding on why the traditional system is problematic and how the mastery system of learning should be designed.

Educators and communities turn to mastery learning for many different reasons. You may be concerned about the emotional health of your students. You may want to find ways to better engage them. You may be concerned about inequity and that too many students aren’t learning what they need to know to be successful. You may be concerned about the economy and want to make sure students are being effectively prepared.

What we all have in common is that we have come to the conclusion that the traditional system is getting in our way. We simply can’t get where we want to go with the traditional system. It was designed in a different cultural, historical, economic, and technological time to serve different purposes.

We have learned over the last 10 years that if we aren’t familiar with the flaws in the traditional system, they come back up and bite us. They undermine the quality of the design and our implementation. To fail to address the beliefs and values that are the foundation of the traditional system is the same as rehabbing a house that is built on a very shaky foundation. Things might be a little bit better, but soon windows won’t be closing properly and water will be leaking into the basement.

For example, the traditional system is built on the belief that intelligence is set in stone; that some students are going to learn and others not so much, so there. This means there is very little teachers can actually do to change the learning and life trajectories of students. We deliver a curriculum and then rank and sort students to determine who gets to go to college. If we don’t challenge the assumption that we know who is smart and who isn’t, that intelligence is fixed, and that schools have responsibility for doing the job for colleges of ranking students, we won’t invest enough in helping the more vulnerable students to learn and we’ll create grading systems that continue to be used to rank students rather than help them focus on their learning.

Another aspect of the traditional system is the belief that students are empty vessels to be filled with knowledge so the job of teachers is delivering curriculum rather than teaching students. A culture of compliance and extrinsic motivation is required to try to get students to do what we want them to do because learning isn’t particularly engaging or fun.

One of the leadership skills that is needed is to identify when these different types of traditional beliefs kick in and become very, very skilled at asking questions to help our colleagues challenge their own beliefs and consider new ones. It’s nearly impossible to change someone’s belief by talking at them. They need be invited to reflect on and test their beliefs in a safe environment.

Implementing Mastery Learning

So what do we replace it with? That’s what mastery learning is all about.

Although it would be great to have, there is no road map for mastery-based learning. At least not yet. We have a pretty good idea of what it should look like, but I’m pretty sure we need to keep working on the overall design. We are still learning.

To help deal with this problem of not having a road map, CompetencyWorks (in 2018 and with the help of practitioners and researchers) developed a logic model to help us think more clearly about what needs to be in place if we want all kids to succeed and that they can actually apply their knowledge and skills.

The logic model starts with clarifying your student success outcomes. What are the knowledge, skills, and traits you want your students to have when they leave your school? It then identifies two main drivers. One is the research on learning and development and the other is committing to equity.

Part of the reason it is proving difficult to create a road map is that there are mediating factors that shape your school and your path forward—these are based on your students and local context.

Let’s consider the student success outcomes and their implications for your design of your mastery-based learning. What do you want students to know and be able to do by the time they graduate? Your school design and the pedagogy need to be designed in a way that reaches these outcomes.

Most likely, you have some mix of these three types of knowledge and skills:

- Academic knowledge and skills will always be important. However, there are some schools and organizations that emphasize skills to such a high degree that knowledge almost disappears from their discussions. This can results in three different kinds of problems: first it is likely that there will be a backlash from parents who value the traditional education system. Second, you are going to risk dumbing down as students may be developing analytical tools without familiarity with the academic concepts. Their analytical skills may stay at a lower level unless they can engage in greater complexity. Third, there is a risk that you are contributing to inequity. Students need to be able to know, remember, and retrieve knowledge easily. Otherwise, they are spending some of their working memory trying to refresh and retrieve concepts when they need it for complex analysis or problem-solving. Investing in helping students learn how to learn facts and concepts is very, very important.

- We know that students need to know how to apply or transfer those skills. They need to know how to use knowledge. They need opportunity to practice, and teachers need to have the capacity to assess at these deeper levels.

- Lifelong learning is a phrase that captures a number of different types of skills and traits. Some schools focus solely on habits and traits such as time management and perseverance. Others might use the term agency or voice or choice. But it is so much more than that. The skills to own one’s own learning means that one can manage one’s thinking and feelings. It includes growth mindset, metacognition, and self-regulation. I’ll refer you to Building Blocks for Learning at Turnaround for Children, as they have strongest framework and research base that I’ve found to date.

These types of lifelong learning skills are critical to any school committed to greater equity. To fail to ensure students develop these skills and traits means that they will continue to be dependent learners. Furthermore, these skills change the nature of power in our classrooms. They are giving students the skills to challenge and navigate any environment, including classrooms where teachers are still burdened with the traditional beliefs.

I’m going to pause here to clarify the use of the concept of personalized learning as it overlaps with lifelong learning skills. I am not talking about technology. If I talk about technology, then I use the term technology. In fact, I’m not going to talk about technology at all… I am talking about personalized learning as a counter concept to the idea of one-size-fits-all or a cookie-cutter approach to education where all students receive the same curriculum and are expected to learn at exactly the same pace. And I am talking about personalized learning in terms of the building blocks for learning.

It’s personalized because it works for me, and it’s personalized because I own it—it’s my mind and my education. Personalized learning means schools are responsible for teaching students all the lifelong learning skills, even at high school.

Now let’s talk about the research on learning and development. I use the word research, not science of learning, as we are still learning about learning. There are gaps in our knowledge. For example, we have a lot more we need to learn about how facts and memories are retrieved. Furthermore, the cognitive science research has been developed within different fields such as neuroscience and education psychology. It’s left to educators to figure out how to build their professional knowledge of how to use different findings from different fields.

Based on all my school visits, I truly believe that it helps immeasurably if schools develop a clear set of core pedagogical principles before they dive too far into implementation. The research helps to keep the WHY we are transitioning to mastery learning clear and opens up a very different level of dialogue among educators that is focused on “what’s best for kids” and not introducing a practice because a paper said to or because other schools are doing it. It aligns your decision-making with “what’s best for kids” and helps you pay attention to quality in everything you do.

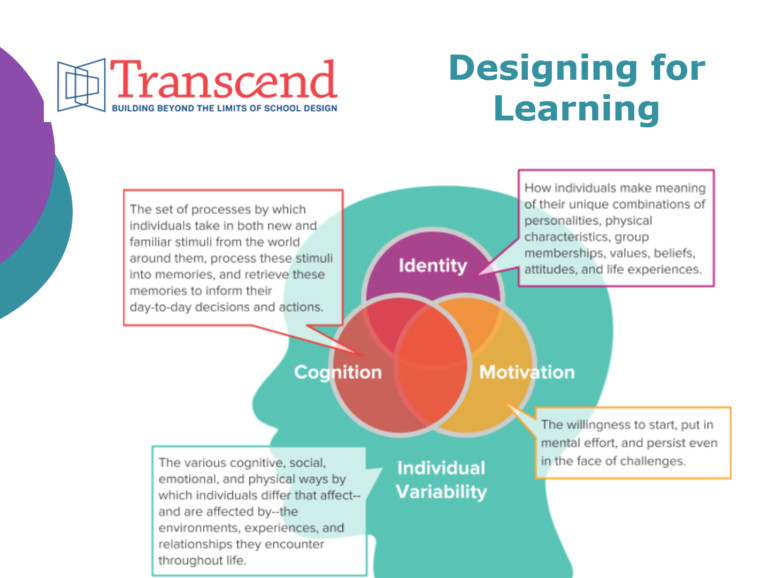

The research on learning is an enormous field with lots and lots of findings, so districts and schools will need to engage teachers in creating a way to make sense of the research. Here is one example. In their paper Designing for Learning, Transcend outlined four main areas of research: cognition, identity, motivation, and individual variability with key findings under each one.

I highly recommend the Transcend paper for a solid summary of the research on learning and development.

However, for our work today, this model developed at CompetencyWorks is a simpler model while still drawing from multiple fields of research. At LearningEdge, you can also find an article with several different resources available on the research on learning and development.

Many of these findings challenge the beliefs of the traditional system. And they definitely put into question the practices of the traditional high school classroom.

Let’s take a look at a few of these findings:

The first one is learning is an activity that is carried out by a learner. Learners have to be actively involved and engaged. The fourth one is that the effort we put forth is dependent on motivation and self-regulation. The fifth one refers to the research on how we process information from working memory to long-term memory that takes into consideration prior knowledge, the fact that we can only work with a maximum of 7 concepts at a time, and that we need practice to encode information.

So why do we think that students are going to be learning just by listening to a teacher talk, taking notes, and periodically being asked to answer a few questions? What the research tells us is that we need to design learning experiences so that students are actively challenged, that we need to provide information in bite-sized pieces with time to allow for students to process and practice, and that we need to pay attention to the conditions of the classroom and school so that students feel safe and aren’t spending their working memory worrying about whether something negative might happen to them. Even in high school, we should be coaching students on metacognition and emotional self-regulation if it is getting in their way of learning.

The quiz is a fascinating and illuminating example about how the traditional system can negatively influence the learning experience. A quiz used as a technique to help students discover what they know and where they need to focus is a powerful tool. In the traditional system that believes that the grade, or extrinsic motivation, is what will inspire students to put forth their best effort, the quiz becomes ineffective. Summative grading may actually diminish motivation and effort. Students will be more motivated and put in more effort if they feel they will eventually be successful. Being judged might lead to students shutting down if they start to feel afraid and not having an opportunity to continue learning will diminish intrinsic motivation.

I want to make one other comment about the research on learning. There is substantial research on how we think and how we retrieve ideas. This research is showing us how bias just jumps into our minds without our even knowing it. And is helping us to understand how we might slow our thinking down and help each other identify bias when it does appear. Thus, this research on learning can help adults reduce implicit bias that is negatively impacting our relationships and our instruction with students….

The Mastery Transcript: Continuous Improvement with a Strong Focus on Equity

Now we are going to look at how you might leverage the Mastery Transcript to put into place core features and then challenge yourself to do it in a way that it is high quality.

The Mastery Transcript is considered a high-leverage practice because it both communicates that something is changing and it is systemic in that it requires other parts of the education system, namely colleges, to change as well AND for schools, you can’t fully implement the mastery transcript without implementing core features of a system of mastery learning in your schools.

- The core idea is to put the focus on learning.

- Broad set of student success outcomes that emphasize knowledge and skills.

- Students will need to demonstrate their learning; A-Fs won’t be used.

- More personalized with students able to pursue learning and demonstrating their learning within high interest contexts.

But if we want a Mastery Transcript, what else needs to be in place?

CompetencyWorks, with the help of 100 practitioners, identified what we think are the distinguishing features. Remember, there are other features of high performing schools and districts. We think these are 10 features that are important to implement with quality.

I’m going to highlight a few that I think are particularly important.

The second one states that districts and schools are committed to making sure that all students master the learning expectations. This means two things: You don’t just pass kids on with gaps. Nor do you retain them. It assumes that a record of what students have mastered and not what is available to teachers and that there are plans for how you help students master the material in the near future. Second, it means continuous improvement with a strong focus on equity. Which students didn’t master the material, why not, and how do you need to change so that the next cohort will?

The third feature is about empowering inclusive cultures of learning. We debated this a lot—a high-achieving culture is important for any school. Most of the literature on high-achieving culture emphasized order. In looking at the research, it became clear that schools need to pay attention to making sure everyone feels like they are included and belong. If you don’t, you don’t feel safe. If you don’t don’t feel safe – if you have fear—your amygdala is going to be activated and will impact learning. We also determined that an empowering leadership style is important—because if students are going to have agency, you better make sure teachers do, as well.

The fourth feature is about consistency…How do you make sure that within your school, teachers are determining mastery with the same expectations? How do you make sure that there is consistency across schools in a district? If there isn’t the same consistent expectations held, we fall right back into inequitable practices with students being passed along without learning what they need to in order to be successful in the next step of their education…

Read More

Interested in reading the complete transcript of Sturgis’s remarks and seeing her presentation slides? Read more on Learning Edge.