Already a member? Log in to the Member Site at members.mastery.org.

Mastery Learning in Action

June 11, 2020Letter to the Editor: Wall Street Journal

June 30, 2020Assessment: What Students Must Learn

Greg Curtis, an expert in school change, participated in MTC's spring Online Member Symposium, delivering two sessions on assessment, designing qualitative learning goals, and reframing the learning environment. The following post is the second in his related MTC Insights “Assessment” series. Read the first article in the series here.

Thank you for joining me for the second installment in this series. We’ll begin to dig into the various shifts that I see as essential to transform a school or district into a mastery-based learning environment. In this piece, I wanted to explore some key points in moving from a Graduate Profile to a Learning Model, as per MTC’s Journey Towards Mastery Learning.

Domains of mastery is a term sometimes used to describe a taxonomy or structure for organizing different grain sizes of essential learning goals. It is not a novel feature and we regularly utilize similar hierarchies to organize academic standards into subject areas, strands, standards, benchmarks, or something similar. In a mastery-based environment, all learning goals should be grouped under a consistent structure to allow us to organize the landscape and create a map to navigate our goals. This is especially true of our transdisciplinary goals.

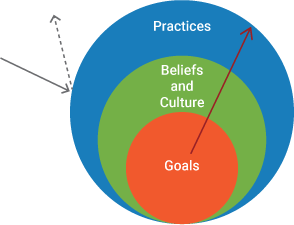

The framework you devise and populate with essential learning goals is a core element to operationalizing a move to mastery. It is also a key element of transformation, especially when we elevate new learning goals as part of this structure. I believe that transformation in education has been difficult because we largely leave the goals of learning untouched. Why change our assessment practices, for example, if we are still assessing the same things and my past practice “did well enough?” Schools have thick skins and efforts to push change in from the outside are often deflected by this skin. However, if we change our goals at the center of our practice, we can effectively drive change backwards through all systems within a learning environment.

The framework you devise and populate with essential learning goals is a core element to operationalizing a move to mastery. It is also a key element of transformation, especially when we elevate new learning goals as part of this structure. I believe that transformation in education has been difficult because we largely leave the goals of learning untouched. Why change our assessment practices, for example, if we are still assessing the same things and my past practice “did well enough?” Schools have thick skins and efforts to push change in from the outside are often deflected by this skin. However, if we change our goals at the center of our practice, we can effectively drive change backwards through all systems within a learning environment.

What Students Must Learn

There are simply too many things that we could ask our students to learn; we need to focus on what we must. Academic standards can sometimes bury us and our students in huge lists of everything that is possible to teach about a discipline. It can become, as the old saying goes, “a mile wide and an inch deep.” The same danger exists with “non-academic” (a dated moniker) elements of mastery (I call them desired “impacts,” but you might call them transdisciplinary, 21st century, or something similar) that we wish our students to demonstrate if we are not informed, targeted and selective.

First the concept of focusing on lifeworthy learning (a term popularized by David Perkins) is largely applied to the glut of content that teachers and students must wade through. Is all of this stuff really worth learning? Is it useful in the long run and does it make a difference in the lives of our students? The Impacts we select as part of our mastery domains should be similarly examined.

I have seen schools deal with the scope of learning possibilities by including all or most of a long list of possible impacts and transdisciplinary goals. It quickly becomes a word salad that no amount of organizing can make usable. The entire community spends more time wrestling with huge lists of vaguely defined words than they would be focusing on a small number of clear, distinct, future-focused, achievable and demonstrable goals.

Five Points

In short, here are a few things to keep in mind when constructing your mastery domains:

I hope these five points have been thought-provoking and help with your processes, either as you develop your domains or reflect on an existing structure. Time spent here will provide a solid foundation for all efforts to come.

During the next installment, I plan to explore some core implications for assessment as schools and districts move towards a mastery learning environment.